Management and care of older prisoners

Management and care of older prisoners

This workshop, run by The Butler Trust, focused on best practice in managing and caring for older prisoners and responding to the challenges of an aging prison population.

This workshop, run by The Butler Trust, focused on best practice in managing and caring for older prisoners and responding to the challenges of an aging prison population.

[For further examples of good practice in this area see the older offenders interest group on good-practice.net.]

“I find four causes for the apparent misery of old age;

first, it withdraws us from active accomplishments;

second, it renders the body less powerful;

third, it deprives us of almost all forms of enjoyment;

fourth, it stands not far from death.”

Cicero (106-43 BC), De Senectute (Of Old Age)

A Growing Problem

Old age, as the saying goes, is not for the faint-hearted. A well-known photograph shows a 73 year old Bette Davis, after four decades of stardom, two Oscars, and ten Oscar nominations, holding up a cushion stitched with the words “Old age ain’t no place for sissies”. Neither is prison.

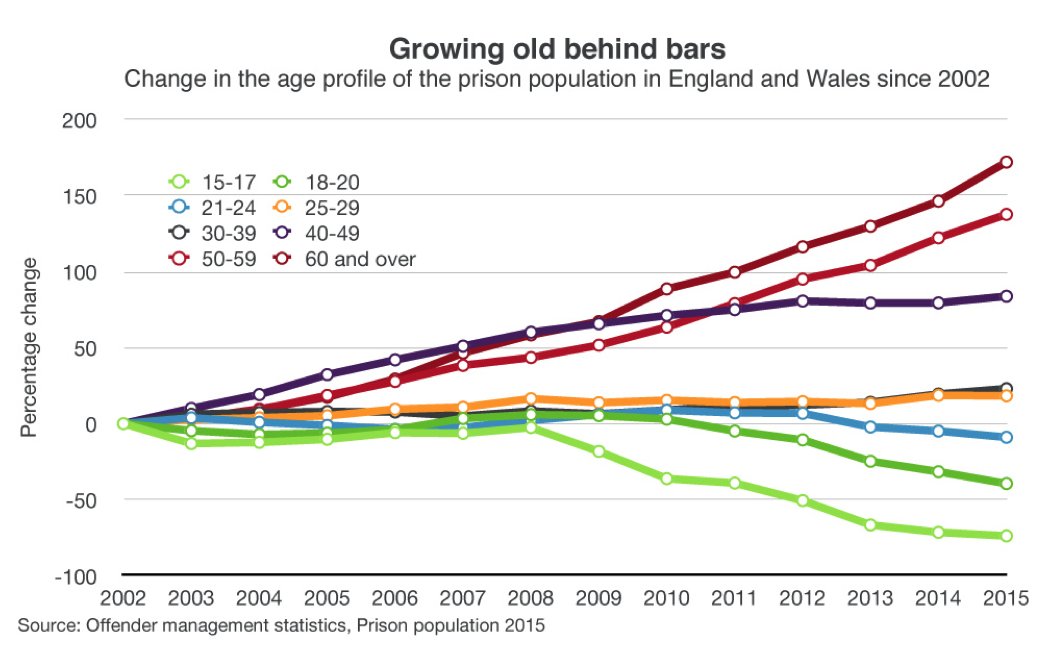

Yet a number of factors, including longer sentences, ageing populations, and historical offences, means British prisons have seen a dramatic increase in the numbers of older prisoners in recent years, as this amply demonstrates:

Our free Butler Trust Good Practice workshop, on the management and care of older prisoners, attracted the usual engaged and informed mix of expert speakers and experienced delegates – many attending on their own time. Typically, the workshop fizzed with a sense of people addressing a serious issue with real dedication and quiet passion.

Our first speaker, Francesca Cooney of the Prison Reform Trust, noted that there were now over four thousand prisoners over 60 – and around 1 in 7 who are over 50. (Cue silent groans from several people not quite willing to recognise 50 as the threshold – although, more seriously, definitions of ‘old’ vary considerably in the literature). She went on to capture the problem with an obvious but still somehow startling observation: “Prisons are really designed for young, healthy men.” [view Francesca’s presentation]

Age-related declines in health, and its cost to both individuals and the system, was, unsurprisingly, a key topic of the day. It’s a complex area, and can include impairment of mental and physical health, disability, social care, personal isolation and loneliness (itself increasingly well-established as having a profound impact on health) as well as end-of-life complications.

Yet one of the more common issues among marginalised people is that, while we often hear about them via experts, academics, policy papers and the media, we tend to hear less in their own voices. (Darron Heads’ spellbinding presentation at last year’s workshop on Offenders with Learning Disabilities proved the point). One of our later speakers, Sandy Umfreville from HMP Exeter, helped correct that with a series of accounts by older prisoners describing the impact of a ‘Buddy’ on their lives. Given that wider understanding remains a crucial issue for all parties, they’re worth reading in detail, and are therefore distributed throughout this write up:

| “My Buddy has been a great help to me. He got me a cell move so that I didn’t have to go up and down stairs anymore. He gets my meals for me and fills my flask up whenever I need him to. He also helps me clean my cell and gets my kit change and helps me make my bed for me. [He] is always checking to see if I am alright and if I need anything. I consider him a friend as well as a great Buddy. I think the Buddy system is a great one and I am grateful for the help I get from it.”

A man, who suffers mental health problems, who had previously tried to commit suicide by jumping off a building and now had locked ankles following numerous operations, and walks on crutches. He is a easy target for bullying and was recently assaulted. He now has a cell opposite his Buddy on the same landing. Source: Sandy Umfreville, HMP Exeter |

Victimisation and bullying of older, vulnerable older prisoners is, unfortunately, another issue of concern. This can be related to generational differences – something as simple as young prisoners’ “music” playing loudly – as well as misunderstandings, or an active refusal to sympathise, for example due to a prisoner serving a term for historical sex crimes.

Nor is this a one-way street: generation gaps are felt on both sides of the ageing equation, both inside prison and in the wider world. Indeed, not only are we all heading towards old age, another country about which we tend to feel ambivalent, the demographic shifts involved in an ageing population structure are slowly but surely becoming evident throughout society. From health and social care costs to accessibility and standards in old people’s homes, from government policy to personal family problems, this set of issues – so pointed in a prison context – ultimately belongs to us all.

Although Francesca’s presentation, and the PRT’s prescient 2008 report, Doing Time: the experiences and needs of older people in prisons, highlighted the problems, she also acknowledged that there was good practice in the system. Indeed, two of this year’s Butler Trust Award winners were honoured for their outstanding work in this field, and both were present to share their experience.

Caring for as well as about

Our next speaker, Paul Goodridge of HMP/YOI Parc (who received his Award along with colleagues Kath Davies, David Griffiths and John Watts) was one of those Butler Trust Award Winners present. There’s a telling quote, by HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, about the work of the Assisted Living Unit (ALU) they’ve developed at Parc that’s been widely picked up: an elderly prisoner in hospital specifically asked to be transferred back to Parc’s ALU “to die among people he knew and who cared not just for but about him.” It’s a quite extraordinary testament to the reality of the best prison work that puts to shame some of the lazier critical voices in the field. Indeed, an HMIP report hailed their “ground-breaking approach” as “the kind of best practice which should be adopted in other prisons in Wales and England.”

Paul’s enthusiasm and dedication shone through his presentation, along with practical and hard-won expertise. Among several professional hats, he leads on “Palliative & End of Life Care and Dementia Pathways” – a notable, complex, and tough aspect of working with older prisoners, as this case study from Sandy highlights:

| “Having been in prison in 2014, in a wheelchair, I begged for help with collecting meals, kit change, bed change, and got nothing. I was abused, bullied and frightened. Since 2015 (when the Buddy service started) I now have a quality of life, food, clothes, help with exercise, Well done, thank you.

I find my Buddy to be attentive, very positive and always helpful and encouraging. He helps me with the tasks I find too difficult to do and also actively encourages me to do what I can for myself. He walks with me to exercise and back and encourages me to go out on exercise. He treats me with respect constantly and is understanding of my health issues and memory problems.” A man with early onset dementia Source: Sandy Umfreville, HMP Exeter |

Paul recounted the “interesting journey” to creating Parc’s ALU. He highlighted the argument that “hospital escorts and bedwatches were a significant drain on resources”, and cited several factors helping drive change:

- Operational staff were overwhelmed, due to a lack of knowledge and understanding

- Staff believed that prisoners with such needs should be managed clinically – while clinical teams believed that it was a social care matter

- Service provision and application was patchy, inconsistent and failed to meet the needs of this population cohort

This resulted in the most vulnerable at a greater risk:

- Older prisoners reported that they felt isolated and withdrew themselves

- Impacted on their mental health

- Increase in negative self worth

Paul’s team tackled a number of classic barriers to change, including ‘buy in’ from the top, managing expectations and, critically in this area, ensuring the right staff were selected and trained for the unusually challenging work. He also emphasised the value of building partnerships with other expert providers in the field, from Macmillan and the Alzheimer’s Society to AgeCymru and Stirling University’s Dementia Centre.

The group took care to ensure their work was underpinned by research, and also rigorously measured their own progress. His top tips from his journey included recognising that “Rome wasn’t built in a day”, taking a “bite-sized” approach to what is a long and complex process, and plugging into “the wealth of knowledge and expertise in the community” – who proved willing to help and engage. Fostering such relationships, he admitted, took time – but he advocated patience and persistence. [view Paul’s presentation; a more detailed write up of his work can also be found here]

Physical and mental

The award-winning Sandy Umfreville of HMP Exeter spoke next. She pointed out practical elements, from “incessant background noise” disorientating those with hearing difficulties, to the plethora of steps, staircases, and doorways too narrow for wheelchairs in many prisons. As well as the built and social environment, she also cited the difficulties of a lack of staff expertise. Her “Buddy scheme” proved transformative, so that “older prisoners who were spending all day, every day, in their cells are now feeling more involved [in prison life].” [view Sandy’s presentation]

As noted, the eloquence of her case studies speaks perhaps most powerfully of all, so here’s another:

| “This scheme is excellent. My Buddy provides the help and support I need to maintain health and hygiene. He covers the day to day tasks I’m unable to do such as cleaning my cell thoroughly and making my bed. He helps at meal times and ensures that I have water, as I scald myself. My Buddy is aware of the difficulties I have and he encourages me to maintain personal hygiene and takes me to ‘F’ wing so that I can use the disabled showers.

I have great difficulty pushing my wheelchair and can manage a few metres only but now I am able to access prison services such as library, education and even fresh air / exercise, thanks to my Buddy pushing me. He ensures that I can access and use the stair lift safely each day. He (gently) reminds me to consider what I eat. Being a wheelchair user I feel vulnerable when the wing is busy and tend to stay in my cell. My Buddy is happy to spend time with me and we share ideas, thoughts, beliefs and anything else I wish to discuss. This makes me feel valued. I can not praise this scheme enough, it alleviates many difficulties I face and helps to retain my dignity. It also lifts my spirits as I know I have support.” Source: Sandy Umfreville, HMP Exeter |

Next, HMP Wakefield’s Neil Evans, a Physical Education Officer, and Janet Richards, an Older Persons Lead Nurse, presented on the challenges of cardiac care in a high security prison. This is another example of the transformative role Physical Education plays in prisons: the subject of one of last year’s Butler Trust Workshops (full report here).

HMP Wakefield has one of the oldest population profiles in the estate – with over half of prisoners over 50, and almost a quarter over 60. For all the centrality of gyms in prison, one of their first tasks was “changing the mind set” of older prisoners that it was “for the young.” Reinventing and reframing activities helped – so four a side football became “walking football” (a relatively new idea, showcased in this recent advert):

Click image or here to view the full advert

Meanwhile the cognitive element of health (as per Juvenal’s motto, ‘Mens sana in corpore sano’ – a healthy mind in a healthy body) was covered with quizzes and so on. This was part of a suite of interventions including education, tackling weight problems, health and wellbeing events, as well as looking at old injuries.

They also noted several compelling arguments, including the resource-heavy costs of inaction:

- Increasing prevalence of chronic disease/illness due to people living longer

- Increasing number of hospital re-admissions following cardiac events

- Security and high risk escorts, needs an upstream approach (prevention is better than cure)

- Issued guidelines for PE departments dealing with prisoners experiencing known cardiac issues accessing gym facilities [PE Bulletin (2009)]

- Inequalities between community and custodial services

(One of the biggest influences on their work, they noted, was a prisoner taking a prison to court because of the poor comparison with the care he could expect in the community).

The results of their approach, which included the critical factors mentioned above of achieving ‘buy in’ and wider understanding, alongside resolving the tensions between ‘care’ and ‘custody’, are quite remarkable: acute cardiac events have been reduced by 60% within 4 years. [view Neil & Janet’s presentation]

Companionship

Next to speak were Paul and Rita Conley, Salvation Army volunteers at HMP Wymott, whose CAMEO (‘Come And Meet Each Other’) project also won a Butler Trust Award this year. Their project, above all, seeks to offer older prisoners “a place of safety”.

‘Old Friend’ by italolemus on Flickr, used with permission under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-ND 2.0

In setting up the centre, they too faced the usual difficulties, from finance to suspicion among the prisoners. Once established, however, the club area also offered “a place for discussion” where they could talk their about issues to each other and Paul and Rita.

It also served as what Paul calls “a place for desperates”, where they could find an sympathetic advocate who could liaise with the system, for example over issues like medication. CAMEO also provided “a place of understanding” – given that being old, overlooked and perhaps confused are normal parts of the ageing process – and realising that this makes an enormous difference. Paul and Rita also find their commitment to a non-judgemental and honest approach helpful.

CAMEO offers a wide range of activities, from education sessions to quizzes, DVDs, and music. (Paul noted that while he’d been playing music from the fifties and sixties, one prisoner asked if they could have some Led Zeppelin. Briefly surprised, he then realised that their heyday, in the early seventies, was over forty years ago). Visitors and guests have ranged from African drummers and a brass band to an undertaker(!), with activities ranging from cheese tasting to making cards.

Emphasising the importance of trust, Rita mentioned a recent member, their oldest prisoner. “He is 94 years old and he laughs every day, he smiles every day.” Another touching anecdote concerned a prisoner who was able to say, as a result of their work, “this is the first time my feet have touched grass in seven years.” Rita concluded with powerful words: “We hope that our CAMEO centre saves lives and serves suffering humanity.” (A more detailed write up of their work is available here).

Our final speakers were Georgina Day and Darren West from HMP Whatton. Their comments, like so many from speakers and audience alike throughout the day, reflected extremely impressive levels of compassion and dedication: Darren emphasised the value of research and opportunities, and looking “for inexpensive solutions to deliver decency for those in our care.”

Georgina described another creative solution, a “dignity line” painted on the corridor of a wing which other prisoners aren’t allowed to cross in order to “give more ‘end of life’ dignity”. As Georgina said, “When you join the prison service as a prison officer, this isn’t what you signed up to do.” That said, she was unstinting in her admiration of those caring for prisoners as patients: “I can’t sing their praises highly enough.”

Like a bookend to Francesca Cooney’s presentation, which also questioned the degree to which elderly prisoners are being released on compassionate grounds, they also spoke of challenging custody-driven decisions, with Georgina asking, “If you’ve got a prisoner dying, do they really need handcuffs?” [view Georgina & Darren’s presentation]

| “My Buddy is the best! He comes every morning as soon as we are unlocked and makes sure I am fit and happy. He copes with my needs and is always happy to be helpful. He pushes me for my meds every morning, he keeps my cell clean and tidy, gets my meals and does everything he can to look after me. I depend on him so much. I can’t walk at all without assistance and I appreciate everything he does and always with a smile. I am 83 years old and he makes my life in here so much better than it was.”

Wing Officer: “I was impressed with the standard of care and concern shown by the buddies towards a palliative care resident on F wing. Although…no longer lucid, two of the buddies would spend time in his room watching the rugby with him and talking to him about it.” Source: Sandy Umfreville, HMP Exeter |

Once again, the Q&As and afternoon sessions showed informed and engaged people sharing good practice. Suggestions and ideas to take back to the workplace bubbled forth with a unusual level of enthusiasm, ranging from brainstorming sessions and ‘age advocates’ to auditing existing accommodation and building an external network of partnerships: the key points from this session are available here.

Of many words spoken on this often emotive subject during the day, the simplicity and power of Darren’s final remark reflects not just where people working in this area are coming from – but also the ethos underpinning so much unsung work in the British prison system: “We think it’s the right thing to do.”

“There is only one solution if old age is not to be an absurd parody of our former life,

and that is to go on pursuing ends that give our existence a meaning.”

Simone de Beauvoir, The Coming of Age

[For further examples of good practice in this area see the older offenders interest group on good-practice.net.]